Centinela

Western Andes, Ecuador

Two kindred spirits in support of this project…

Conserve.org is excited to partner with Canadians Rylie Denis and Tristan La Haye as they embark on a global bikepacking and surfing expedition to educate and advocate for the protection of this forest.

Tristan and Rylie are advocating to protect land and expand the Centinela Reserve in Ecuador, one of the planet’s thriving cloud forests, while journeying through the Americas.

We will share updates on Tristan and Rylie's journey, from Canada all the way to Centinela, Ecuador.

Rylie Denis

From Kamloops, British Columbia“I grew up deep in the ski-bike culture of BC, but always felt drawn to surfing. I spent time learning my way around the waves in Australia and Instructed in Tofino. More recently I have earned a diploma in Adventure guiding, and reconnected with my passions for art and languages.

I've always wanted to embark on a journey worth writing about, one that requires connection with the land and the people who steward it.”

“Heya! I'm a Canadian ski patroller, tree planter and environmental advocate. With an Adventure Guiding diploma and a deep love for movement and exploration, I’m driven to embark on a journey that challenges and enhances my connection with the world around me.

We want to use our outreach to protect land, giving back to the earth that gives us so much. Learn more about our conservation efforts!”

From Knowlton, QuebecTristan La Haye

Donate to permanently conserve land in Centinela, Ecuador

Conserve in your name, or… let us know who you’d like to honor.

They will receive a Gift Email with photos and coordinates of the protected acreage, and you will receive a copy of the message.

Your donation pays for the cost to buy land in Centinela, Ecuador, at market rate, and place it in a permanent land trust managed by local Ecuadorian non-profit ‘Jocotoco.’ Your donation will receive a match of 100% from non-profit Art into Acres. The 2025 cost of cloud forest land is $112.00 per acre.

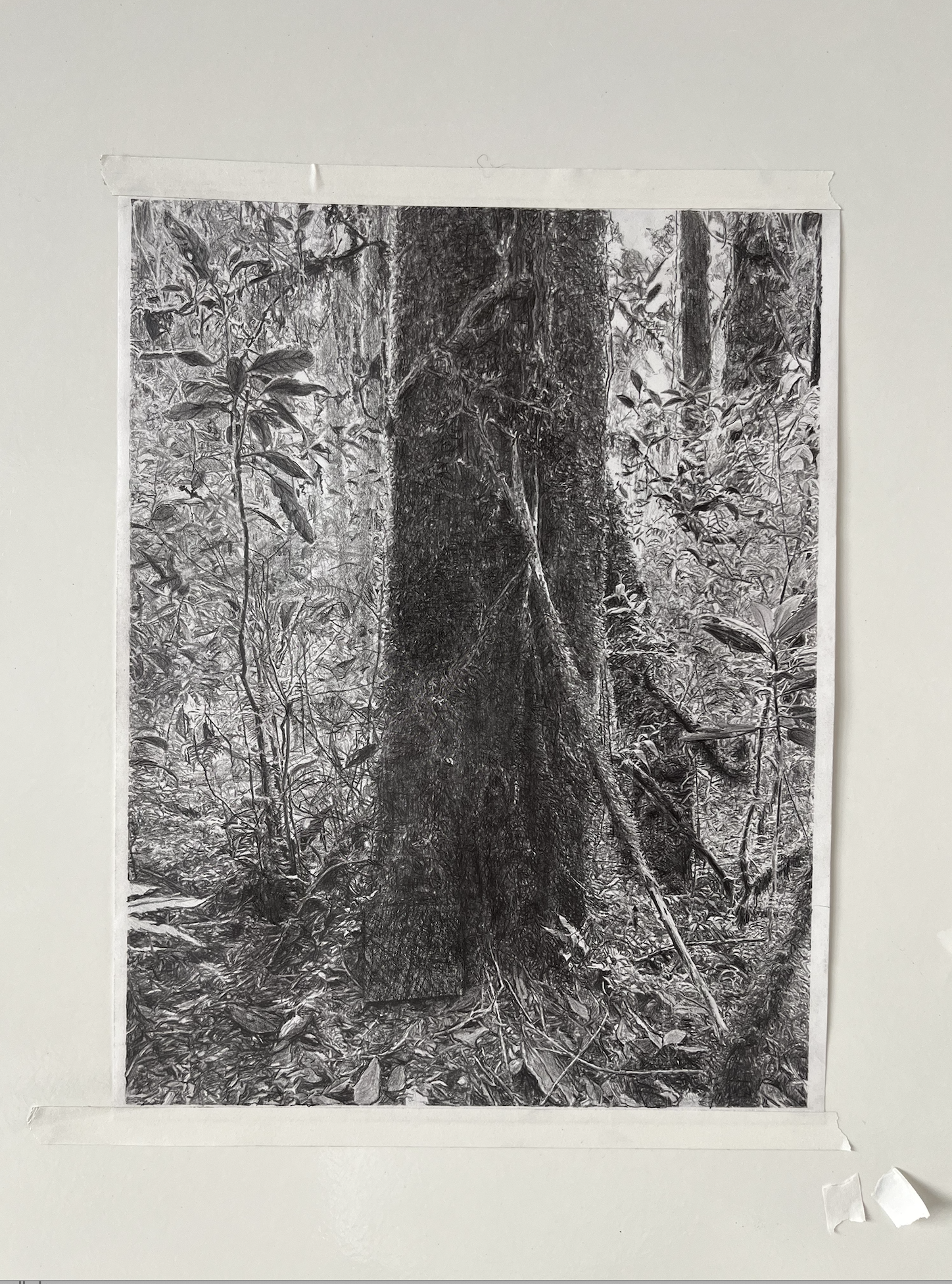

Morning fog over the Centinela, Santo Domingo de los Tsachilas province, Western Ecuador.

Project Ambassadors:

Rylie Denis and Tristan La Haye

Type of Protection:

Private reserve

Conservation Partners:

Jocotoco, Re:wild

Ecoregion:

Northwest Andean Montane forests

Scale of the Area:

150 hectares - 371 acres

Total Declaration Cost:

$33,750

Home to these rare species:

Annona conica (Endangered)

Browneopsis macrofoliolata (Known only from Centinela; Critically Endangered)

Carapa megistocarpa (Endangered)

Cremastosperma stenophyllum (Endangered)

Daphnopsis grandis (Endangered)

Dracontiuum croatii (Endangered)

Drymonia laciniosa (Endangered)

Eschweilera podoaquilae (Endangered)

Gasteranthus extinctus (Critically Endangered)

Gasteranthus otogensis (Vulnerable)

Geissanthus fallenae (Endangered)

Genoma tenuissima (CR → Endangered)

Gustavia dodsonii (Endangered)

Matisia coloradorum (Endangered)

Matisia palenquiana (Endangered)

Quararibea calycoptera (Endangered)

Randia carlosiana (Endangered)

Sciodaphyllum pilarense (New species known only from Centinela; provisionally Endangered)

Swartzia decidua (Endangered)

About the project stewards:

Local Ecuadorian communities and young conservationists

About the local conservation partner:

Jocotoco is an Ecuadorian non-profit foundation. It currently manages ~100,000 acres in 17 bioreserves throughout Ecuador. They averted the extinction of the once critically endangered species the Pale - headed Brushfinch, which had an extinction probability of 89%. Similarly, they brought two critically endangered trees species back from the brink of extinction, increasing their populations more than tenfold within three years.

Jocotoco restored forests by planting 1.7 million trees of 140 native species. Within just one human generation (25 years), wildlife returned to these once desolated places in a diversity that matches that seen in old-growth rainforest. This quick recovery demonstrates that we can fully and quickly restore even the arguably most complex ecosystem on Earth. Because of this recovery, apex predators such as Jaguars, Pumas, Spectacled Bears, and Harpy Eagles have returned to areas where they were previously hunted out. The only viable population of Jaguars in Western Ecuador is now found in Jocotoco’s largest reserve.

Grant Research, Care and Diligence Team:

Dr. Martin Schaefer, Jocotoco; Dr. Chris Jordan, Re:wild: Dr. Andy Lee, Resolve: Dr. Haley Mellin, Conserve

Rare Species (Conservation Imperatives) Site:

Yes

Ecological History

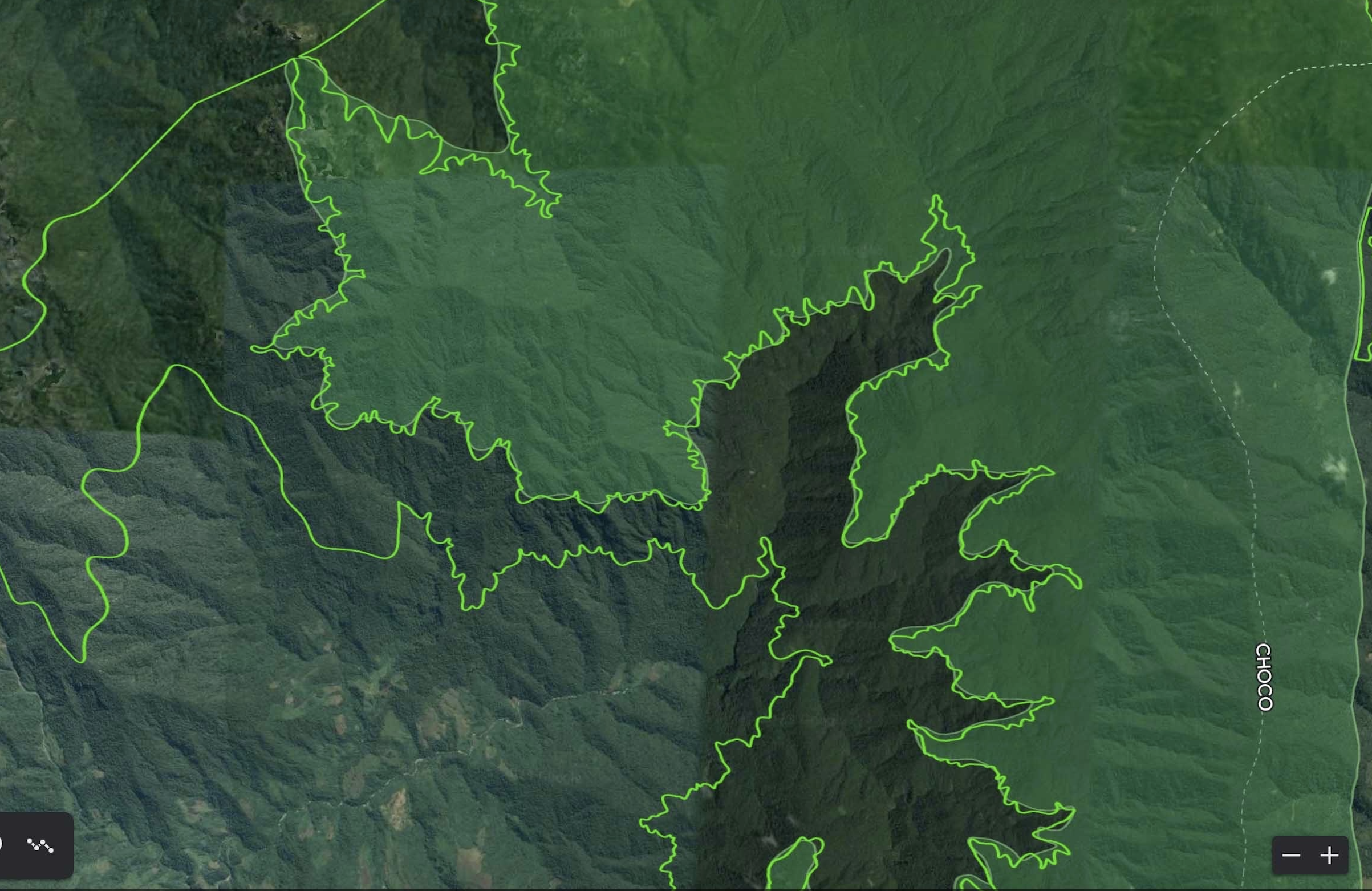

The Northwestern Andean montane forests ecoregion extends along the Cordillera Occidental (Western Range) of the Andes in Colombia and the Cordillera Occidental of Ecuador. It covers an area of 8,132,562 hectares (20,096,000 acres). In the extreme north the ecoregion merges into the Magdalena–Urabá moist forests ecoregion. Through most of its length in Colombia it transitions on the west into the Chocó–Darién moist forests and on the east into the Cauca Valley montane forests. The higher levels of the ecoregion give way to Northern Andean páramo. It almost completely surrounds the Patía Valley dry forests. In its southern section the ecoregion transitions into the Western Ecuador moist forests to the west and the Eastern Cordillera Real montane forests to the east. The southern end of the ecoregion transitions into the Tumbes–Piura dry forests ecoregion.

The ecoregion is in the neotropical realm, in the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome. It is part of the Northern Andean Montane Forests global ecoregion. This ecoregion contains the Magdalena Valley montane forests, Venezuelan Andes montane forests, Northwestern Andean montane forests, Cauca Valley montane forests, Cordillera Oriental montane forests, Santa Marta montane forests, and Eastern Cordillera Real montane forests terrestrial ecoregions. The cooling during glacial periods isolated plants and animals adapted to warmer climates into isolated pockets, while the cooler zones expanded and became connected. During the warmer inter-glacial periods the warmer zones rose higher and reconnected, while the cooler zones became isolated. The result was steady formation of new species, creating high levels both of diversity and endemism.